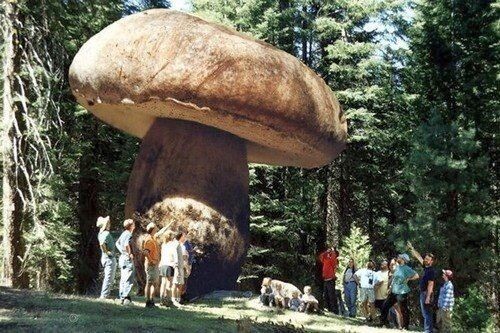

The Amillaia ostoyae, commonly referred to as the honey mushroom, sprouted from a minuscule spore too tiny to be transported by the wind. Over an estimated span of 2,400 years, it has been stretching its mycelium filaments across the forest, resulting in the shedding of trees’ leaves.

Spanning across 2,200 acres through tree roots, this fungus holds the distinction of being the largest living organism ever discovered.

“When you’re on the ground, the pattern isn’t immediately evident; you simply observe clusters of dead trees,” remarked Tina Dreisbach, a botanist and mycologist collaborating with the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Research Station in Corvallis, Oregon.

This 2,400-year-old mushroom stands as the largest living organism on Earth.

Resembling a mushroom in structure, this colossal fungus spans an outline that extends across 3.5 miles and delves approximately three feet into the ground, covering an area as vast as 1,665 football fields. Its weight, however, remains unestimated.

Discovery Through Decaying Trees

In 1998, Catherine Parks, a scientist at the Pacific Northwest Research Station in La Grande, Ore., stumbled upon this revelation. She received information about a significant tree die-off due to root decay in the forest east of Prairie City, Ore.

Using aerial shots, Parks surveyed a region of dying trees and collected root samples from 112 of them.

Through DNA testing, she identified the fungus, subsequently determining that 61 of the samples originated from the same organism. This revelation indicated that a single fungus had grown larger than previously believed.

The Armillaria ostoyae Fungus Reigns as Earth’s Largest Lifeform

In arid climates, the fungus remains microscopic, visible only through clusters of golden mushrooms that surface with the fall rains.

“They’re edible, but the taste isn’t the greatest,” remarked Dreisbach. “I’d recommend adding lots of butter and garlic to improve their flavor.”

Upon uncovering the roots of an affected tree, observers note a substance resembling white latex paint. These formations are actually mats of mycelium that draw water and carbohydrates from the tree, disrupting its nutrient absorption.

A favorable dry climate can indeed promote fungal growth.

Rhizomorphs, the black shoestring filaments, extend as long as 10 feet into the soil, infiltrating tree roots through a combination of pressure and enzymatic action.

Scientists are deeply engaged in understanding how to manage Armillaria as it poses a threat to trees. However, they are gradually recognizing that the fungus has served a purpose in nature for millions of years.